# having 0 Heads in 2 coin tosses:

choose(n=2,k=0) # (0,0)[1] 1# having 1 Heads in 2 coin tosses:

choose(n=2,k=1) # (0,1), (1,0)[1] 2# having 2 Heads in 2 coin tosses:

choose(n=2,k=2) # (1,1)[1] 1On this page you will find some examples and code for probability distributions.

In your take-home exam, you will NOT be tested on programming (e.g. simulation) or theoretical results. Content on this page is to help you understand the math behind topics in the next days.

A random sample is random. For example, if you throw a 6 sided dice twice, you will possibly have different outcomes. This process can be simulated with the line below.

You can copy and paste this line to your R console, and run it a few times. Alternatively, click on Run Code button below a few times. You should see different results every time.

By setting the seed in programming, it means you fix the process of the random data generator. This ensures that your results is reproducible regardless of when you run the line below.

You can try to set a different value of the seed number, say set.seed(20) and see what happens!

The randomness in the data generating process implies that if you simulate two datasets with the same parameters, the output could be different, even though both are from the same theoretical distribution.

Binomial distribution has two parameters: \(n\) and \(p\). In R, they are referred to as size and prob. Consider the following process:

The probability associated with each possibility can be described by binomial distribution (n,p).

You will see the notation \({n \choose k}\) in the formula of binomial distribution. This is the binomial coefficient, it is the number of ways to pick up \(k\) elements from a total of \(n\); or, having \(k\) number of successes in \(n\) experiments.

In 2 coin tosses, each one toss can have 2 outcomes (write as 1, 0 as Heads and Tails). There are in total 4 possibilities: (0,0), (0,1), (1,0), (1,1)

The number of scenarios corresponding to zero 1, one 1, two 1’s are (1, 2, 1). In R, you can use commmand choose(n, k) to find these three values.

[1] 1[1] 2[1] 1Similarly, if you want to find out in 3 coin tosses, how many scenarios (or combinations) can give zero, one, two and three 1’s,

We can start with simulating 500 random sample from a binomial distribution whose parameters (n,p) are (1, 0.5). This is like tossing a fair coin once (n=1), whose probability of having Heads and Tails are 50/50 (p=0.5). We toss it 500 times, and record each time what outcome it is.

We can print out the first 20 results, and visualize all the frequencies from the 500 outcomes.

Here you see that the frequency for 1 and 0 outcomes are very close to 0.5, even though sometimes there are slightly more 1 than 0 and vice versa.

The X-axis should be only two discrete values - 0 and 1; and nothing between.

For a random variable \(X\) and parameters \(n, p\), the formula of binomial distribution is

\[P(X = k) = {n \choose k}p^{k}(1-p)^{n-k}\] Here \(k\) is the number of success (1’s) among \(n\) experiments. For example, \(n=5\), the possible range of \(k\) could be 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 successes. The number of successes is affected by the probability \(p\) for each one experiment - in general, the higher \(p\) is, the more likely you get larger number of successes. This can be seen from the histogram.

You can experiment with different combinations to see the effect of size and prob, N and P. Try the following combinations:

In the lecture we used 8 patient contracting a disease with probability of 0.15 as example. We computed the probability of having 2 patient getting the disease. Let \(X\) be the random variable denoting the number of patients having disease; \(P(X = 2)\) is when this number equals to 2.

Using the formula of binomial distribution, plugging the numbers:

\[P(X = 2) = {8 \choose 2}0.15^{2}(1-0.15)^{8-2}\] In R,

# probability: p=0.15

# total patients: n=8

# x (or k) = 2, 2 getting disease

p <- 0.15

choose(8, 2)*p^2 * (1-p)^(8-2)[1] 0.2376042This is equivalent to using the R command rbinom(x, size, prob),

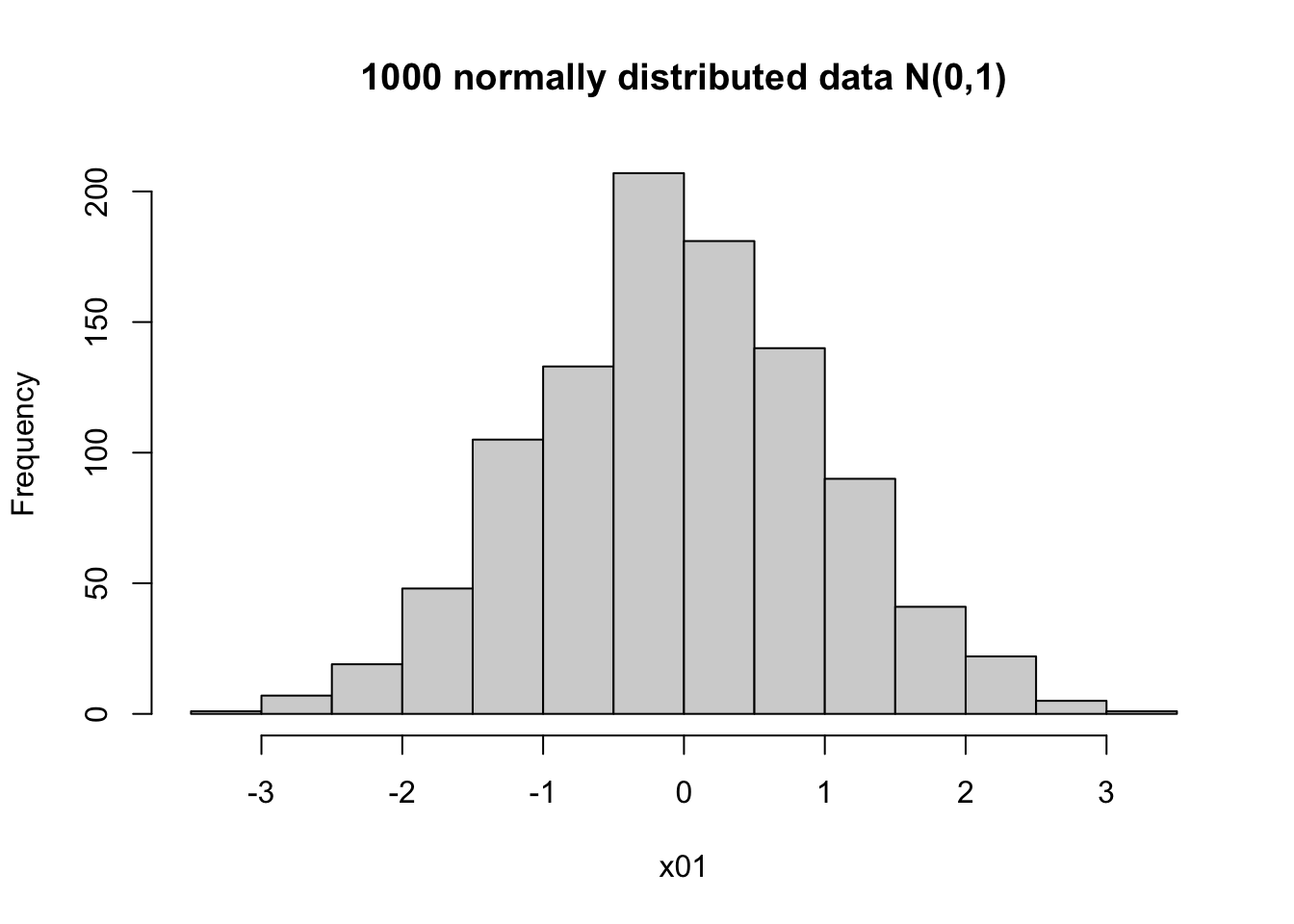

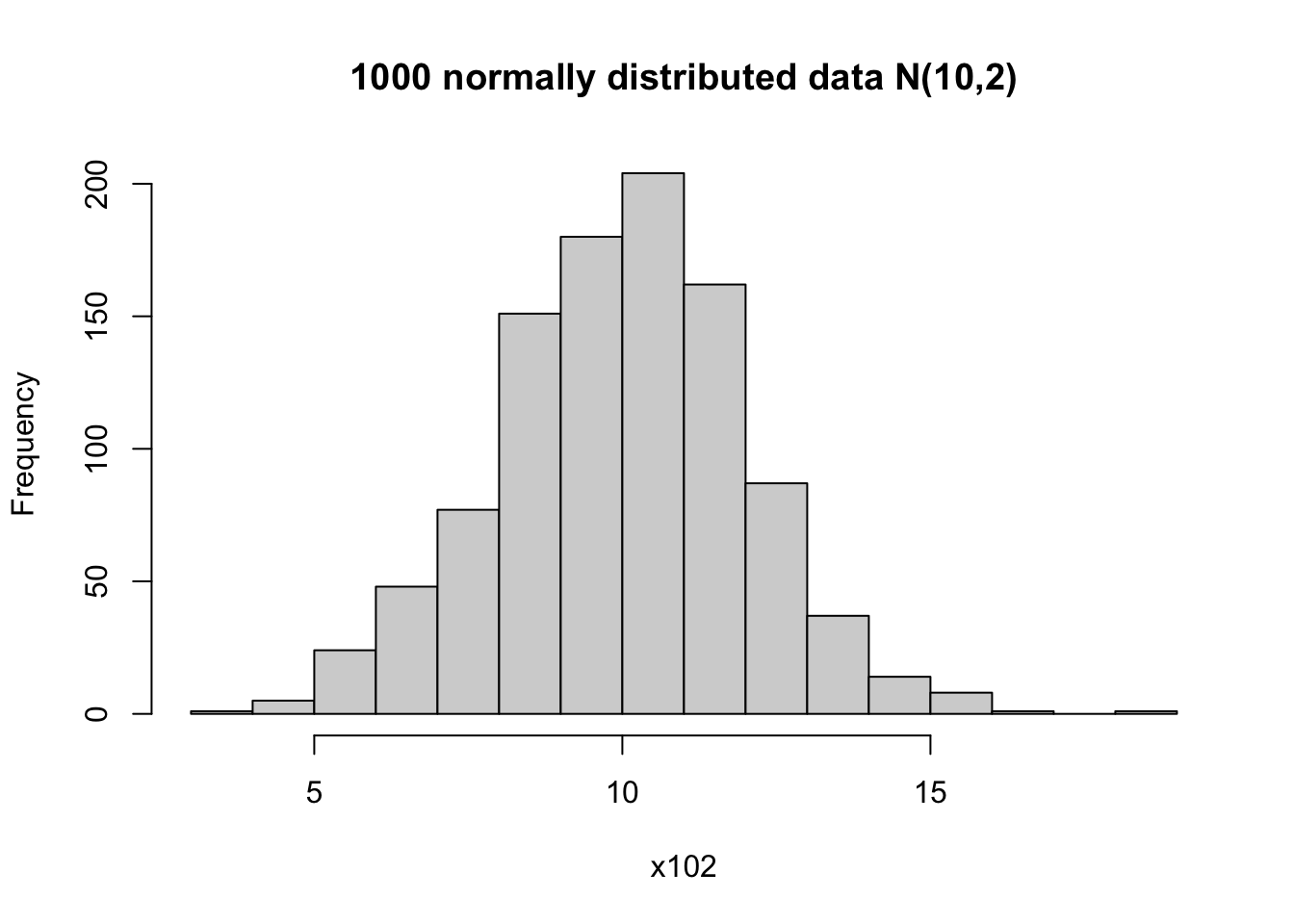

The normal distribution has a bell-shape, and is symmetrical. In a simulation, it might not look perfectly symmetrical; but when you have a large enough sample, it should be close enough to a bell-shaped histogram.

# two parameters: mean and sd

x01 <- rnorm(1000, mean = 0, sd = 1)

hist(x01, main = '1000 normally distributed data N(0,1)')

You can find the summary statistics for the simulated data.

Min. 1st Qu. Median Mean 3rd Qu. Max.

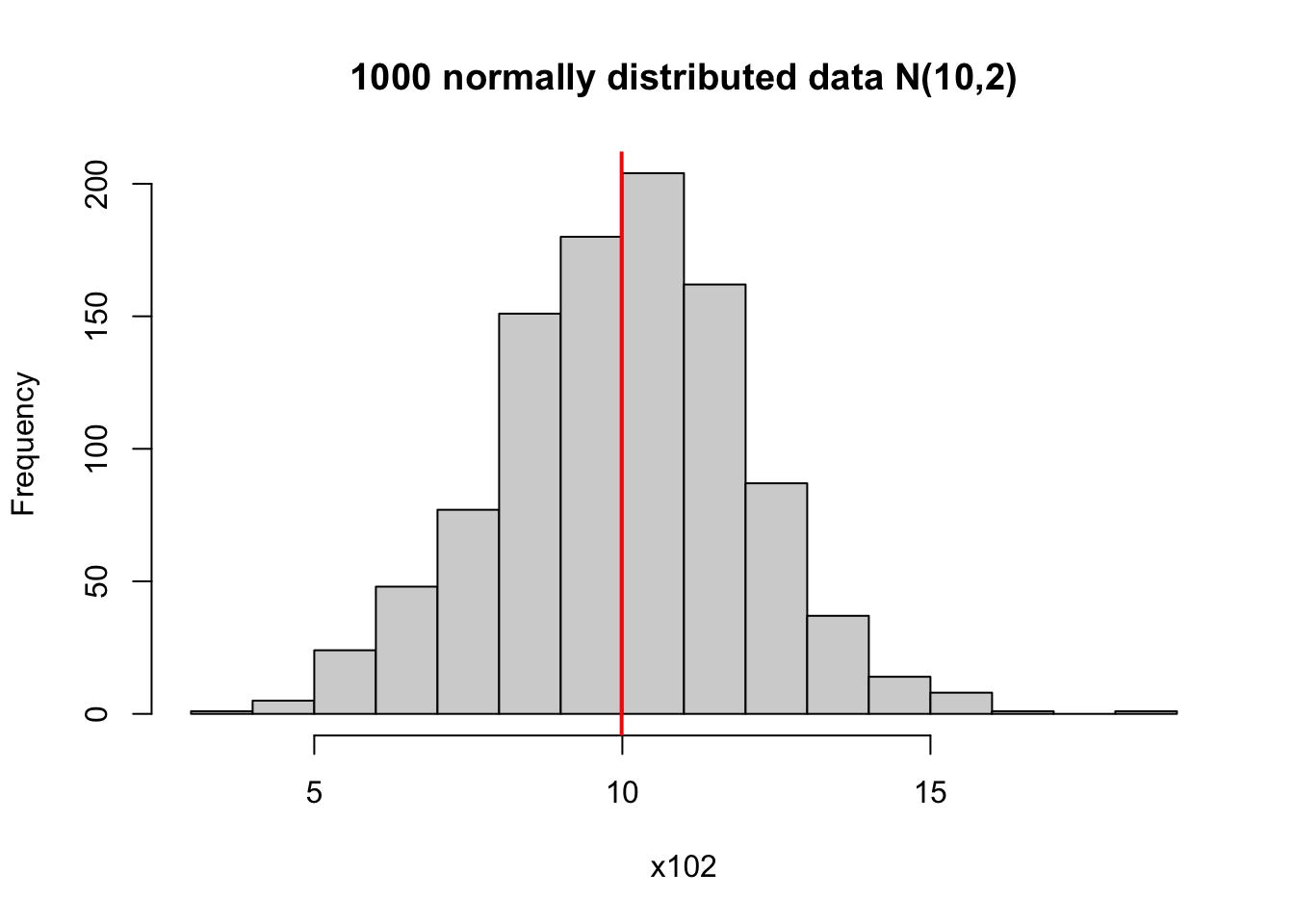

3.983 8.615 10.065 9.988 11.348 18.008 [1] 9.988159[1] 4.108443[1] 2.026929It can be helpful to visualize the mean on top of the histogram.

# can plot the mean on the histogram to indicate the center

hist(x102, main = '1000 normally distributed data N(10,2)')

# v means verticle line, lwd means line width

abline(v = mean(x102), col = 'red', lwd = 2)

For a standard normal distribution, its 2.5% and 97.5% quantiles (\(\pm 1.96\)) are frequently used. This means that

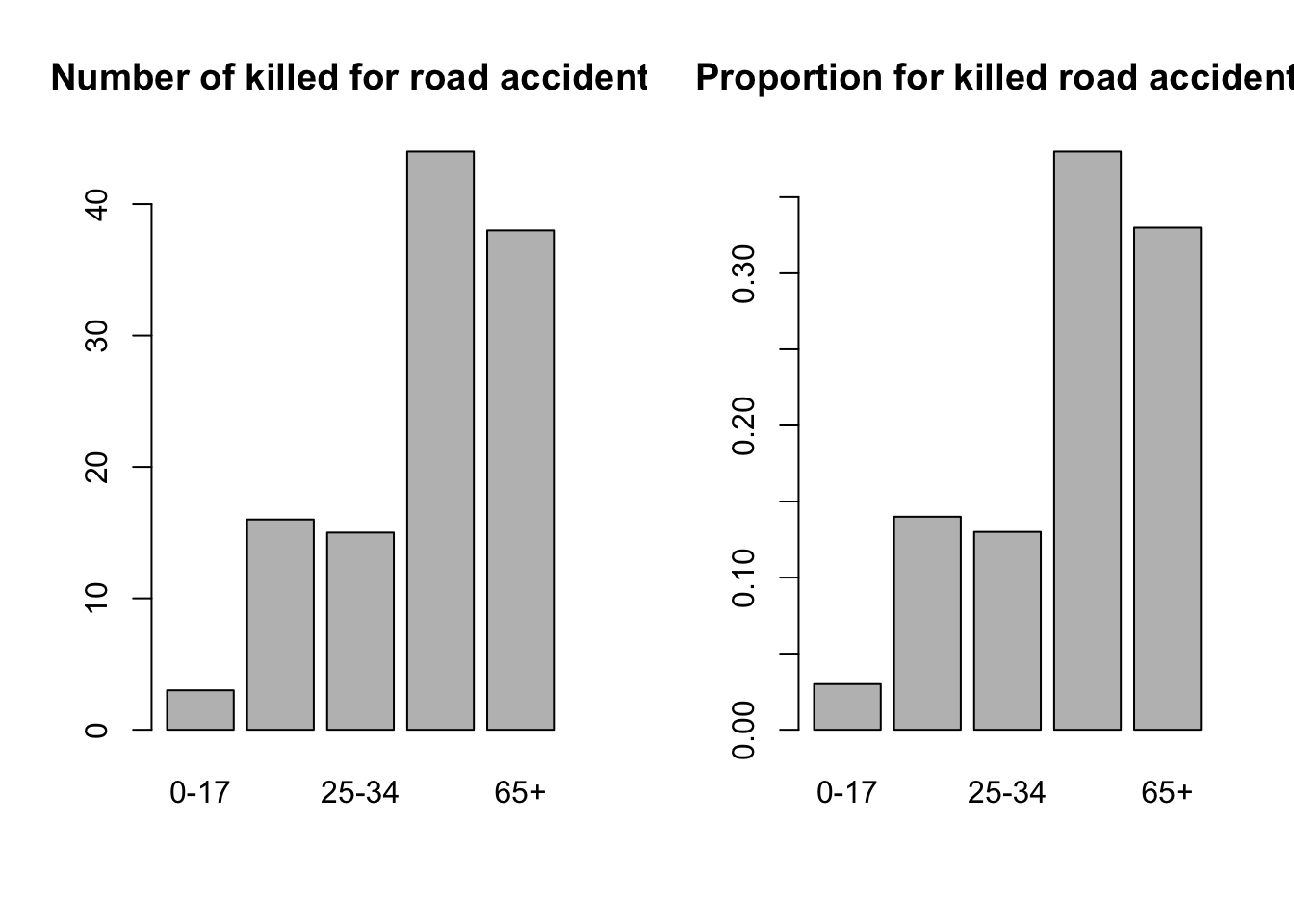

When you have data in groups, you can plot them in a bar plot.

dd <- data.frame(prob = c(0.03, 0.14, 0.13, 0.38, 0.33),

n = c(3,16,15,44,38))

rownames(dd) <- c('0-17', '18-24', '25-34', '35-64', '65+')

# we can plot two graphs side by side

# set parameter: 1 row 2 columns

par(mfrow = c(1, 2))

# bar plot for counts

barplot(dd$n, names.arg = rownames(dd),

main = 'Number of killed for road accidents')

# bar plot for probability

barplot(dd$prob, names.arg = rownames(dd),

main = 'Proportion for killed road accidents')

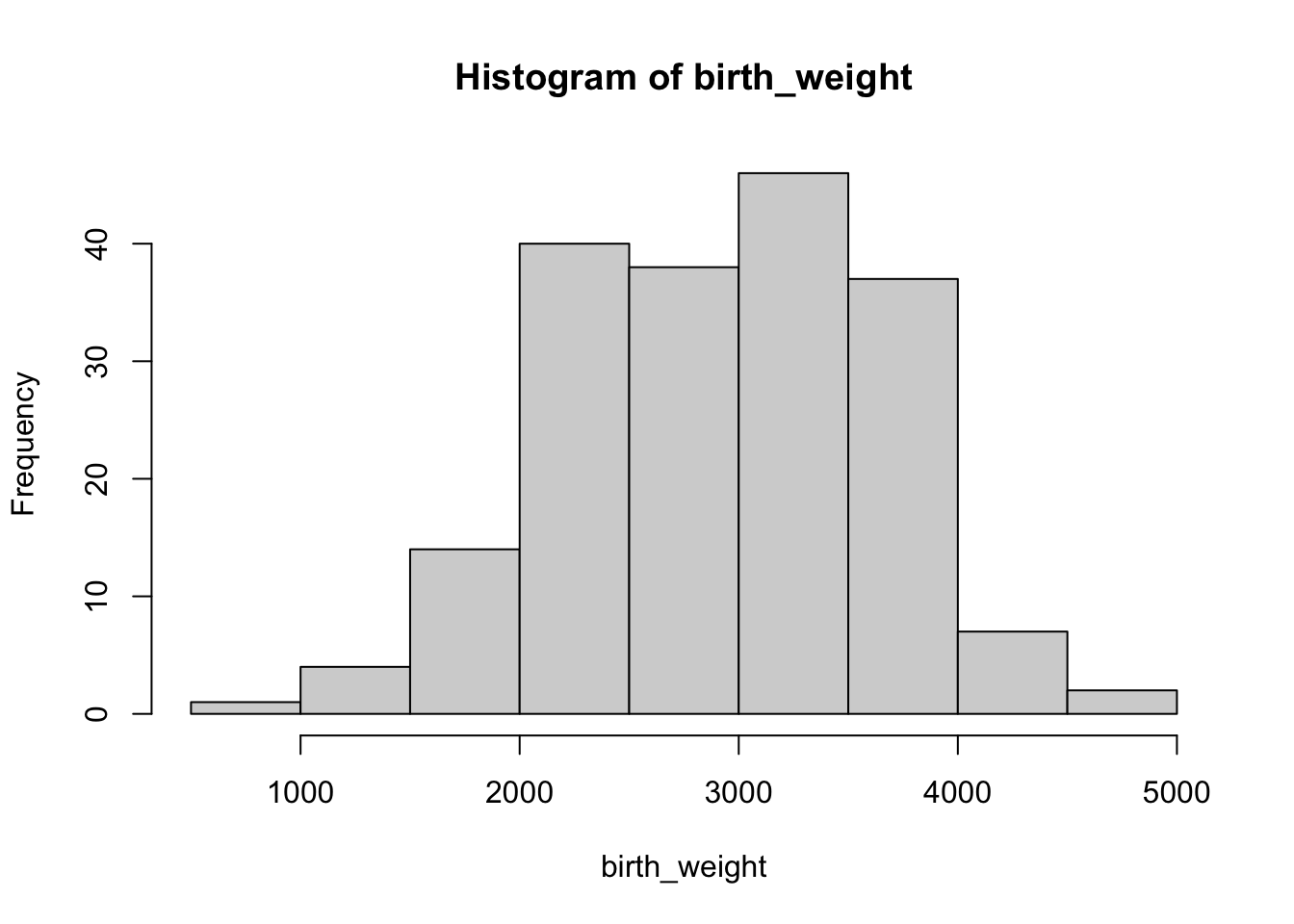

This is the example we used in class to illustrate normal distribution. We are going to reproduce the example in class: explore birth weight variable, bwt. Our task is to estimate the probability (or proportion) for birth weight above 4000g.

Load the data birth.csv (or another data format). You can use the point-and-click in Rstudio to load the dataset.

Create a variable called birth_weight by extracting the bwt column, using the dollar sign operator. Make a histogram of this variable.

# load birth data first

# if you forgot, check notes from day 2 (descriptive stat)

birth <- read.csv('data/birth.csv', sep =',')

head(birth) # print 6 rows id low age lwt eth smk ptl ht ui fvt ttv bwt

1 4 bwt <= 2500 28 120 other smoker 1 no yes 0 0 709

2 10 bwt <= 2500 29 130 white nonsmoker 0 no yes 2 0 1021

3 11 bwt <= 2500 34 187 black smoker 0 yes no 0 0 1135

4 13 bwt <= 2500 25 105 other nonsmoker 1 yes no 0 0 1330

5 15 bwt <= 2500 25 85 other nonsmoker 0 no yes 0 4 1474

6 16 bwt <= 2500 27 150 other nonsmoker 0 no no 0 5 1588

You can count how many data points fits your criteria: weight above 4000. Let us assume that this is strictly above, hence equal to 4000 is not considered.

[1] FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE

[13] FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE

[25] FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE

[37] FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE

[49] FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE

[61] FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE

[73] FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE

[85] FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE

[97] FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE

[109] FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE

[121] FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE

[133] FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE

[145] FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE

[157] FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE

[169] FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE

[181] TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE# we see 9 TRUE. you can print out the birth_weight values to check if it's the case

# 'which' finds the indices for TRUE

which(birth_weight >4000)[1] 181 182 183 184 185 186 187 188 189[1] 9R treats the logical values TRUE as 1 and FALSE as 0; so you can also do mathematical operation such as sum directly.

Since the variable birth_weight looks similar to a normal distribution, we can also use normal approximation for this task. First we should find out the parameters for this distribution, by estimating the mean \(m\) and standard deviation \(s\).

Afterwards, there are two options:

# first get the parameters mean and sd (or sqrt variance)

m <- mean(birth_weight)

s <- sd(birth_weight)

c(m, s) # print out[1] 2944.6561 729.0224# s <- sqrt(var(birth_weight))

# probability of birthweight above 4000

# directly from N(2944, 729)

# lower.tail = F means it computes p(X>4000)

pnorm(4000, mean = m, sd =s, lower.tail = F)[1] 0.07386235# you can also use the standard normal dist

# whose mean and sd (var) are 0 and 1

# can be translated as a second variable Y above 1.45

# see lecture notes for why this is the case!

# hint: (4000-m)/s

pnorm(1.45, lower.tail = F)[1] 0.07352926Under certain conditions, binomial distribution can be approximated by a normal distribution. Try out different values of \(N, P\) to see when the approximation breaks!

For example, start with

---

title: "Binomial and Normal distribution"

engine: knitr

format:

html:

code-fold: false

code-tools: true

editor: source

filters:

- webr

webr:

channel-type: "post-message"

---

On this page you will find some examples and code for probability distributions.

::: callout-note

In your take-home exam, you will NOT be tested on programming (e.g. simulation) or theoretical results. Content on this page is to help you understand the math behind topics in the next days.

:::

## Randomness and simulation (optional)

A random sample is **random**. For example, if you throw a 6 sided dice twice, you will possibly have different outcomes. This process can be **simulated** with the line below.

You can copy and paste this line to your R console, and **run it a few times**. Alternatively, click on **Run Code** button below a few times. You should see different results every time.

```{webr-r}

#| label: rand1

#| warning: false

#| echo: true

# take two numbers from 1,2,3,4,5,6

# replace = T means the same number can appear in both first and second

sample(1:6, size = 2, replace = T)

```

By **setting the seed** in programming, it means you fix the process of the random data generator. This ensures that your results is **reproducible** regardless of when you run the line below.

You can try to set a different value of the seed number, say `set.seed(20)` and see what happens!

```{webr-r}

#| label: rand2

#| warning: false

#| echo: true

# if set seed, the result is the same

# you need to run the line set.seed(yourseed) right before

set.seed(1)

sample(1:6, size = 2, replace = T)

```

The randomness in the data generating process implies that if you simulate two datasets with the same parameters, the output could be different, even though both are from the same theoretical distribution.

```{webr-r}

#| label: rand3

#| warning: false

#| echo: true

# 100 standard normal distributed data

x1 <- rnorm(100, mean = 0, sd = 1)

head(x1) # prints the first 6 values

summary(x1) # prints the summary statistic for these data

hist(x1, main = '100 random samples from N(0,1)')

```

## Binomial distribution

Binomial distribution has two parameters: $n$ and $p$. In R, they are referred to as `size` and `prob`. Consider the following process:

* an experiment or trial has two outcomes: 1 and 0; positive or negative; boy or girl; ...

* the probability of having 1 as outcome (or 'success') is $p$

* repeat the experiment $n$ times, where each one experiment does not affect the other (independent)

* count how many times there are zero 1's, one 1's, ..., n 1's

The probability associated with each possibility can be described by binomial distribution (n,p).

### Binomial coefficient in R

You will see the notation ${n \choose k}$ in the formula of binomial distribution. This is the binomial coefficient, it is the number of ways to pick up $k$ elements from a total of $n$; or, having $k$ number of successes in $n$ experiments.

In 2 coin tosses, each one toss can have 2 outcomes (write as 1, 0 as Heads and Tails). There are in total 4 possibilities: (0,0), (0,1), (1,0), (1,1)

* zero 1, only when both are Tails, (0,0);

* one 1, it can be either the first (1,0), or the second coin toss (0,1);

* two 1's, only when both are 1, (1,1)

The number of scenarios corresponding to zero 1, one 1, two 1's are (1, 2, 1). In R, you can use commmand `choose(n, k)` to find these three values.

```{r}

#| label: bincoef1

#| warning: false

#| echo: true

# having 0 Heads in 2 coin tosses:

choose(n=2,k=0) # (0,0)

# having 1 Heads in 2 coin tosses:

choose(n=2,k=1) # (0,1), (1,0)

# having 2 Heads in 2 coin tosses:

choose(n=2,k=2) # (1,1)

```

Similarly, if you want to find out in 3 coin tosses, how many scenarios (or combinations) can give zero, one, two and three 1's,

```{r}

#| label: bincoef2

#| warning: false

#| echo: true

# having 0, 1, 2, 3 Heads in three coin tosses:

choose(n=3,k=0) # (0,0,0)

choose(n=3,k=1) # (1,0,0), (0,1,0), (0,0,1)

choose(n=3,k=2) # (1,1,0), (1,0,1), (0,1,1)

choose(n=3,k=3) # (1,1,1)

```

### Coin toss example

We can start with simulating 500 random sample from a binomial distribution whose parameters (n,p) are (1, 0.5). This is like tossing a fair coin once (n=1), whose probability of having Heads and Tails are 50/50 (p=0.5). We toss it 500 times, and record each time what outcome it is.

We can print out the first 20 results, and visualize all the frequencies from the 500 outcomes.

```{webr-r}

#| label: binom1

#| warning: false

#| echo: true

# run the code chunk a few times

x <- rbinom(n = 500, size = 1, prob = 0.5)

# first 20 outcomes

x[1:20]

# how many 1 and 0? proportion?

table(x)

table(x)/500

# plot frequency

hist(x, main = 'Histogram of binom(1, 0.5)')

```

Here you see that the frequency for 1 and 0 outcomes are very close to 0.5, even though sometimes there are slightly more 1 than 0 and vice versa.

The X-axis should be only two discrete values - 0 and 1; and nothing between.

### Different n and p

For a random variable $X$ and parameters $n, p$, the formula of binomial distribution is

$$P(X = k) = {n \choose k}p^{k}(1-p)^{n-k}$$

Here $k$ is the number of success (1's) among $n$ experiments. For example, $n=5$, the possible range of $k$ could be 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 successes. The number of successes is affected by the probability $p$ for each one experiment - in general, the higher $p$ is, the more likely you get larger number of successes. This can be seen from the histogram.

You can experiment with different combinations to see the effect of size and prob, N and P. Try the following combinations:

* N: 1, 5, 8, 20, 50, 100

* P: 0.15, 0.5, 0.8, 0.95

```{webr-r}

#| label: binom2

#| warning: false

#| echo: true

# try set different values, run the code chunk a few times

n_sample <- 500

N <- 1

P <- 0.15

# first 20 outcomes

x[1:20]

# how many of each outcomes? proportion?

table(x)

table(x)/500

x <- rbinom(n = n_sample, size = N, prob = P)

hist(x)

```

### 8 patient example

In the lecture we used 8 patient contracting a disease with probability of 0.15 as example. We computed the probability of having 2 patient getting the disease. Let $X$ be the random variable denoting the number of patients having disease; $P(X = 2)$ is when this number equals to 2.

Using the formula of binomial distribution, plugging the numbers:

$$P(X = 2) = {8 \choose 2}0.15^{2}(1-0.15)^{8-2}$$

In R,

```{r}

#| label: binom3

#| warning: false

#| echo: true

# probability: p=0.15

# total patients: n=8

# x (or k) = 2, 2 getting disease

p <- 0.15

choose(8, 2)*p^2 * (1-p)^(8-2)

```

This is equivalent to using the R command `rbinom(x, size, prob)`,

```{r}

#| label: binom4

#| warning: false

#| echo: true

dbinom(2, size = 8, prob = 0.15)

```

## Normal distribution

The normal distribution has a bell-shape, and is symmetrical. In a simulation, it might not look perfectly symmetrical; but when you have a large enough sample, it should be close enough to a bell-shaped histogram.

```{r}

#| label: norm1

#| echo: true

# two parameters: mean and sd

x01 <- rnorm(1000, mean = 0, sd = 1)

hist(x01, main = '1000 normally distributed data N(0,1)')

x102 <- rnorm(1000, mean = 10, sd = 2)

hist(x102, main = '1000 normally distributed data N(10,2)')

```

You can find the summary statistics for the simulated data.

```{r}

#| label: norm2

#| warning: false

#| echo: true

# check the summary

summary(x102)

# mean

mean(x102)

# variance and sd

var(x102) # (sd(x102))^2 # these two are equivalent

sd(x102)

```

It can be helpful to visualize the mean on top of the histogram.

```{r}

#| label: norm3

#| warning: false

#| echo: true

# can plot the mean on the histogram to indicate the center

hist(x102, main = '1000 normally distributed data N(10,2)')

# v means verticle line, lwd means line width

abline(v = mean(x102), col = 'red', lwd = 2)

```

### Important values

For a standard normal distribution, its 2.5% and 97.5% quantiles ($\pm 1.96$) are frequently used. This means that

* probability below -1.96 is approximately 0.025 (2.5%)

* probability above 1.96 is approximately 0.025; below 1.96 is 1-0.025 = 0.975

* probability between $\pm 1.96$ is approximately 95%.

```{r}

#| label: norm4

#| warning: false

#| echo: true

# pnorm finds the probability below a value

p1 <- pnorm(-1.96, mean = 0, sd = 1)

p2 <- pnorm(1.96, mean = 0, sd = 1)

c(p1, p2) # print the values

1-p1 # equal to p2

qnorm(0.025, mean = 0, sd = 1) # 2.5% quantile

qnorm(0.975, mean = 0, sd = 1) # 97.5%

```

## Bar plot

When you have data in groups, you can plot them in a bar plot.

```{r}

#| label: bar1

#| warning: false

#| echo: true

dd <- data.frame(prob = c(0.03, 0.14, 0.13, 0.38, 0.33),

n = c(3,16,15,44,38))

rownames(dd) <- c('0-17', '18-24', '25-34', '35-64', '65+')

# we can plot two graphs side by side

# set parameter: 1 row 2 columns

par(mfrow = c(1, 2))

# bar plot for counts

barplot(dd$n, names.arg = rownames(dd),

main = 'Number of killed for road accidents')

# bar plot for probability

barplot(dd$prob, names.arg = rownames(dd),

main = 'Proportion for killed road accidents')

```

## Example: birth weight

This is the example we used in class to illustrate normal distribution. We are going to reproduce the example in class: explore **birth weight** variable, `bwt`. Our task is to **estimate the probability (or proportion) for birth weight above 4000g**.

Load the data `birth.csv` (or another data format). You can use the point-and-click in Rstudio to load the dataset.

Create a variable called `birth_weight` by extracting the `bwt` column, using the dollar sign operator. Make a histogram of this variable.

```{r}

#| label: birth1

#| warning: false

#| echo: true

# load birth data first

# if you forgot, check notes from day 2 (descriptive stat)

birth <- read.csv('data/birth.csv', sep =',')

head(birth) # print 6 rows

# we use the variable bwt

birth_weight <- birth$bwt

hist(birth_weight)

```

### By counting

You can count how many data points fits your criteria: weight above 4000. Let us assume that this is strictly above, hence equal to 4000 is not considered.

```{r}

#| label: birth2

#| warning: false

#| echo: true

birth_weight>4000 # converts 189 values to T/F indicator

# we see 9 TRUE. you can print out the birth_weight values to check if it's the case

# 'which' finds the indices for TRUE

which(birth_weight >4000)

# length counts the number of elements, here it is 9

length(which(birth_weight >4000)==T)

```

R treats the logical values `TRUE` as 1 and `FALSE` as 0; so you can also do mathematical operation such as sum directly.

```{r}

#| label: birth3

#| warning: false

#| echo: true

# alternatively, since R codes T as 1 and F as 0

# we can use sum() command

sum(birth_weight>4000)

# probability is 9 over total subjects

9/189

```

### Use normal approximation

Since the variable `birth_weight` looks similar to a normal distribution, we can also use normal approximation for this task. First we should find out the parameters for this distribution, by estimating the mean $m$ and standard deviation $s$.

Afterwards, there are two options:

* estimate $P(X>4000)$ when $X \sim N(m, s)$

* estimate $P(Y>\frac{4000-m}{s})$ when $Y \sim N(0,1)$

```{r}

#| label: birth4

#| warning: false

#| echo: true

# first get the parameters mean and sd (or sqrt variance)

m <- mean(birth_weight)

s <- sd(birth_weight)

c(m, s) # print out

# s <- sqrt(var(birth_weight))

# probability of birthweight above 4000

# directly from N(2944, 729)

# lower.tail = F means it computes p(X>4000)

pnorm(4000, mean = m, sd =s, lower.tail = F)

# you can also use the standard normal dist

# whose mean and sd (var) are 0 and 1

# can be translated as a second variable Y above 1.45

# see lecture notes for why this is the case!

# hint: (4000-m)/s

pnorm(1.45, lower.tail = F)

```

## Binomial vs Normal distribution

Under certain conditions, binomial distribution can be approximated by a normal distribution. Try out different values of $N, P$ to see when the approximation breaks!

For example, start with

* N: 10, 20, 50, 100

* P: 0.1, 0.5, 0.8

```{webr-r}

#| label: binnorm

#| warning: false

#| echo: true

# the approximation is N(np, np(1-p)) if n is large, p close to 0.5

# note: the small n (first argument) is how many random samples you want

# it is different from the 'size' argument in binomial distribution

N <- 50

P <- 0.5

# binom(50, 0.5)

x_binom <- rbinom(n = 1000, size = N, prob = P)

# normal

x_norm <- rnorm(n = 1000, mean = N*P, sd = sqrt(50*P*(1-P)))

# plot them side by side

# note that sd for normal distribution is approximate

par(mfrow = c(1, 2))

hist(x_binom, main = 'Binomial (N,P)')

hist(x_norm, main = 'Normal (NP, NP(1-P))')

# take summary statistics

summary(x_binom)

summary(x_norm)

# variance. if want standard deviation, use sd(x)

var(x_binom)

var(x_norm)

```